Rethinking The Changi Crowd Controversy

Published

June 15, 2023

By

Neo Xiaoyun

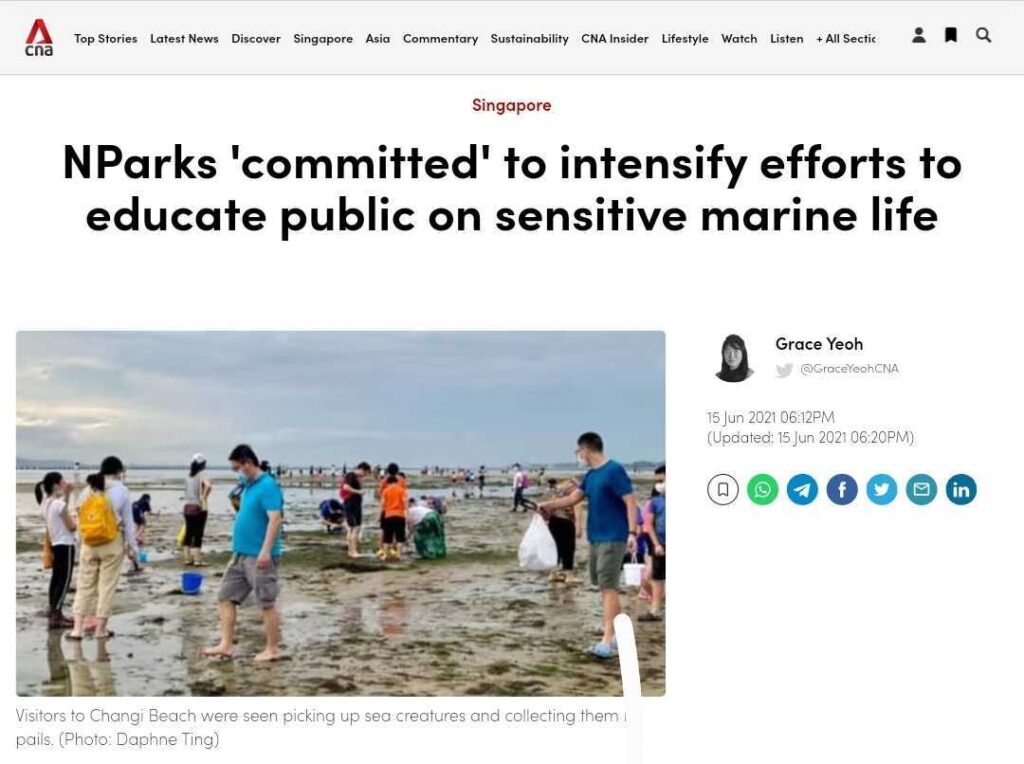

I penned down this piece almost two years ago, at the height of the controversy surrounding the crowd at Changi Beach (mostly Carpark 6) who were seemingly picking up marine creatures and collecting them in their buckets. It begun with an indignant video that showed an overwhelming crowd at Changi, continued into public mobbing (often directed at a particular foreign nationality), endless social commentary within my marine educator circles, hand wrangling, multiple roundtable discussions, physical interventions by intertidal guides and NPark volunteers in the coming weeks, and ended in the crowd dying off as air travel resumed. While I did not want to add my voice back then, some distance has done this piece good. I find that the personal lessons and reflections I’ve penned within remain relevant and important to consider for the next incident that involves the public, the wildlife community, and the green and blue spaces we share in common.

Key Perspective Shifts

It is easy to villianise and jump to conclusions. I felt upset and angry too. As I discussed, read and reflected, I’ve settled on a few more perspectives to this complex issue, which I think should not be forgotten. Recognising and defining the multifaceted problem is important because it then determines what we set out as potential and holistic solutions.

1. The crowds are not a regular occurence, and accessible intertidal areas such as Changi Beach constitute an extremely small fraction of the entirety of Singapore's coasts.

Every day there are two high tides and two low tides. However not every “low tide” is low enough to walk (waters could still be 0.7 – 1 meter which is unconducive). Still more low tides take place in odd hours such as very early mornings, or on weekdays, which attracts only the die-hard intertidal explorers or fishermen. All in all, the intertidal zone is truly stressed for only a few days a month. Nature does get the time and space to rejuvenate.

We assess only what we can see, and we get extremely concerned. However, in fact, much of our coastlines and marine environments remain out of bound, such as Chek Jawa, Sisters’ Island and 92.5 per cent of mainland coasts, due to sea walls and other inaccessible embankments1. With so few opportunities to become attached to local coastal spaces, it’s understandable that we get upset over the mistreatment of one.

The question is, what are we doing, or not doing to protect the remaining 92.5 per cent that we do not see.

2. We need to see this incident in the light of other more significant threats to the marine ecosystem and web of life. This has been elaborated in The Hidden Trials and Tribulations of Marine Creatures.

3. Segmenting the profiles on the beach, we should recognise the presence of communities practicing their traditional livelihood of foraging.

As Syazwan and Firdaus of @wansubinjournal and @oranglaut.sg point out, a blanket ban on foraging would be inappropriate if the community has been practicing their cultural heritage of foraging and fishing in moderation and with respect for ecological limits.

The issue of rough handling is, paraphrasing Dr Neo Mei Lin, no longer a matter of raising awareness, but about education to mend a gap in ethics — the respect for life other than human beings. There is therefore much to learn from the indigenous and traditional lifeways of foraging. Foraging seeks reciprocal relationships with the non-human life involved, for instance harvesting only mature adults and releasing any juveniles or pregnant females. This ensures that one’s community which is so dependent on the marine environment can continue to co-exist, harvest and sustainably consume marine resources in generations to come.

The sense of a land ethic and this respect for ecological balance must be made mainstream somehow. It could start from appreciating and learning from communities that have successfully sought reciprocal relationships with the non-human web of life around them.

4. It's been heartening and refreshing to see the concern during the marine rough-handling episode.

I want to focus on how there seems to be some change and concern for animal welfare: the episode revealed that Singaporeans are able to exhibit care and concern for the welfare of marine animals — even if they are invertebrates.

In the parliamentary debates leading to the passing of the Wild Animals and Birds Act (WABA) in 2020, the newspaper reported that Mr Louis Ng, who forwarded the WABA, had to clarify to the House that “the intent of the law is not to criminalise the killing and trapping of pests and non-threatened invertebrates, as such activities do not undermine the overall aim of wildlife protection”. Louis’ grouping and framing of “non-threatened invertebrates” which would naturally include marine creatures alongside urban “pests” such as cockroaches and ants jumped out to me. Back then, Mr Ng had to set out that the scope of protection excluded non-threatened invertebrates.

In 2021, the discourse had shifted from a previous generic lumping of all “invertebrates” with “pests” to show some level of intuitive empathy across the community for these marine critters that have no backbones. There was a general sense that human actions of rough handling do cause stress and that the animal does feel pain, and that is a surprising moral shift, which would support conservation. After all the web of life is interconnected and the ecosystem does need so-called “non-threatened” marine invertebrates at the base and middle of food webs to support larger (charismatic, protected and threatened) species such as dolphins, days, sharks and dugongs.

5. Finally, here are my personal takeaways in terms of learning and exchanging strategies on how to communicate about contentious human-wildlife interactions in Singapore.

I keep returning to one big lesson from my “Theory and Practice of Environmental Policy Making” module: Framing matters. Instead of “what do you intend to do with the animal?”, to which a member of public can either ignore us or say “none of your business”, we can ask, “Is this animal going to survive if you do xyz?” The latter would likely work by how its framing invites a response. It comes across as genuinely curious and wondering, which gives the person space to answer.

Ultimately, even as we care enough to intervene in a rough handling situation, we have to leave space for the other party to respond. It’s a conversation, not an attempt to corner or appear morally superior. Punitive stances or moral high-grounding would not only be unconstructive, but also possibly invite a hardened stance, as the other party shuts down from conversing.

This is a complex matter. However, I believe that if we can take the hard lessons, it would be a constructive platform for marine educators and volunteer patrols to engage in restorative conversations about respectful, enjoyable and safe human-wildlife interactions in Singapore.

1 William Jamieson, “There’s Sand in My Infinity Pool: Land Reclamation and the Rewriting of Singapore,” GeoHumanities 3, no. 2 (2017): pp396–413. As cited in Novak Sarah, “To Build a City-State and Erode History: Sand and the Construction of Singapore.” Eating chilli crab in the Anthropocene (2020) eds Schneider-Mayerson Matthew, pp61—78