The Hidden Trials and Tribulations of Marine Creatures

Published

February 8, 2023

By

Neo Xiaoyun

Being close to the Coral Triangle, Singaporean waters are home to diverse marine creatures — dolphins, turtles, eagle rays, and a staggering array of beautiful invertebrates from octopus, nudibranch, sea stars, sea cucumbers to ascidians. Life thrives in corals reefs, seagrass meadows, as well as rocky and sandy shores.

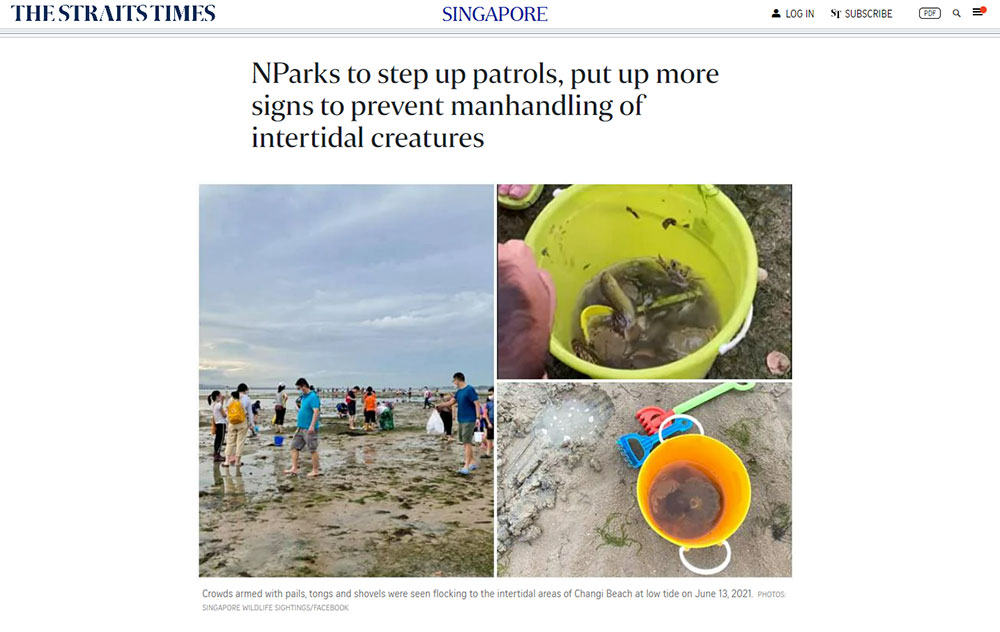

In 2021, a sensational Facebook post and ensuing article about the behaviours of some visitors at the intertidal zone attracted nation-wide attention and spotlight.

Significant as it seemed, this was but one of the multiple stresses faced by the marine and intertidal environments and creatures in Singapore. This article covers some of the factors and pressures that life in the intertidal zone face.

Bleached smooth sea cucumber (Acaudina sp.) and pink warty sea cucumber (Cercodemas anceps). The C. anceps is still feeding with its tentacles, in the bottom right of the picture!

Rainfall and Extreme Weather

During heavy rainfall months, I often witness bleached sea creatures. While still alive, they are weakened from the stressors of abrupt changes in the local environment — be it sea surface temperatures or drop in salinity from a sudden influx of heavy rain.

Prolonged heavy rainfall with its influx of freshwater also caused mass die-offs in Chek Jawa between December 2006 and January 2007. Volunteers reported smelling death in the air. The cause: heavy rainfall which amplified the output of freshwater from the Johor River discharging into the seas surrounding the low-lying intertidal environment of Chek Jawa. While marine invertebrates are generally resilient to daily fluctuations and changes in salinity as well as temperatures, the sudden and accelerated drop in salinity could have caused great physiological stress and subsequent death.

Climate change has in recent years slowly increased the intensity and frequency of heavy rainfall events in Singapore. Although these rainfall events are arguably also human-caused, virality has a pattern and preference for clear villains and direct causal chains.

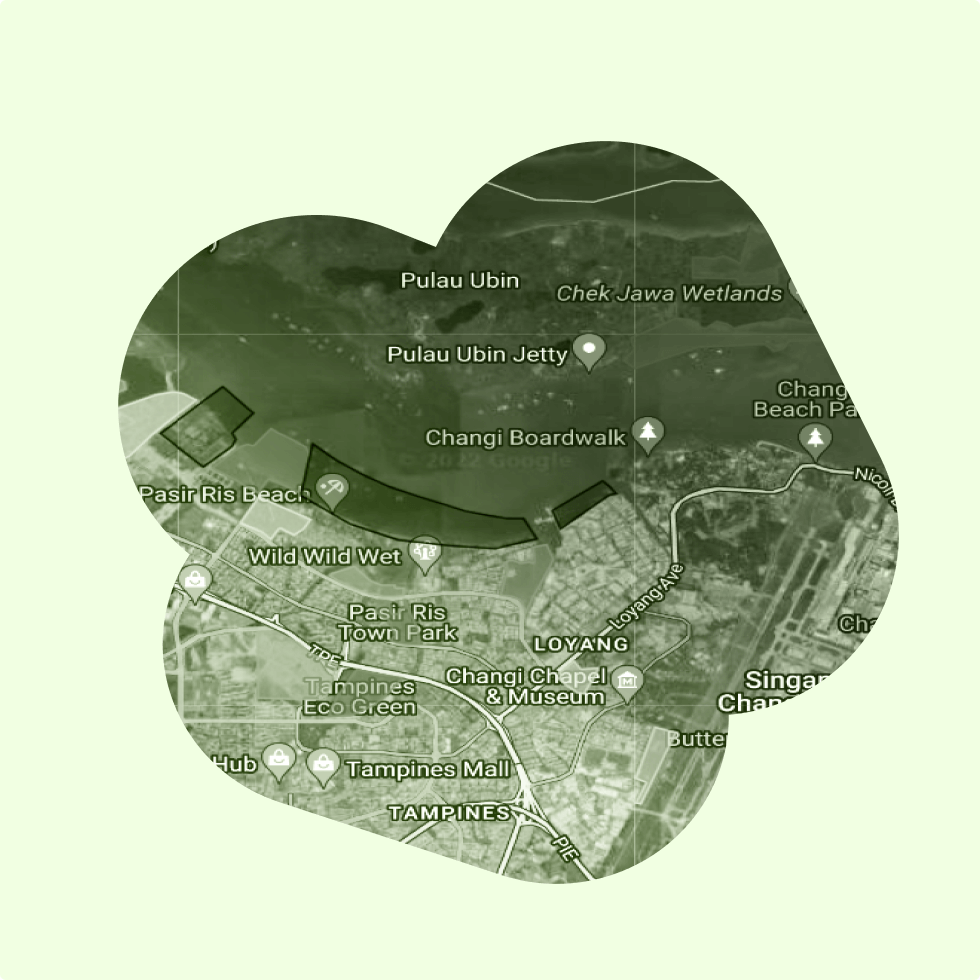

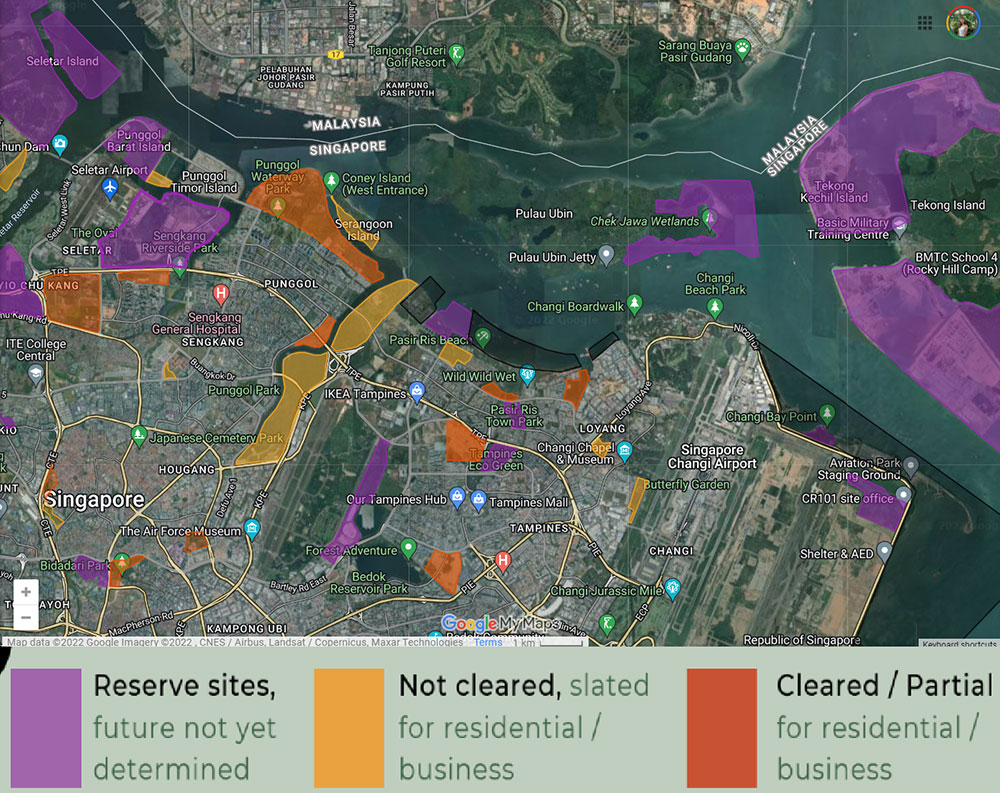

Source: Google Maps

Land Reclamation and Coastal Developments

Drastic as they seem, the bleached intertidal creatures do stand a fair chance of recovery if weather conditions stabilise. A recent study also reassured that only 22 species have been confirmed as invasive species from a compilation of 3,650 marine invertebrates, fishes and plants.

However, marine ecosystems face a longer-term threat. According to the 2013 Land Use Plan, proposed reclamation sites will bury Pasir Ris shores, Pulau Sekudu and Chek Jawa as well as the Changi Beach shores from Carpark 6 to Carpark 7, by 2030. As the summary report by local environmental advocates @LepakinSg notes grimly, we need to protect the shores of Singapore, not just from indiscriminate handling, but also from irreversible reclamation and development.

Land reclamation has already led to the loss of over 95% of our mangroves, 60% of our coral reefs and many of our original coastlines. With land reclamation being very much part of Singapore’s national narrative, a conversation about land reclamation’s discongruity with human and environmental well-being is a tricky one to hold. I pen more thoughts about land reclamation here.

Potential Threat of Invasive Species

Singapore’s excellent location sets itself up as a global shipping hub, with a yearly average of 140,000 vessels calling at its port. However, global shipping is also responsible for facilitating the movement of many marine creatures around the world that become invasive in their new environment. This is because ships take in water from their port of origin (called ballast water) to help ensure that the ship is stable and balanced. Port invasiveness happens when the ship reaches its destination and releases this ballast water with accompanying marine animals, without treating the ballast water prior to release.

Invasive species are so named because they often can multiply rapidly and compete with native species for resources such as food and shelter. A clear example in local waters is the American brackish-water mussel (Mytella strigata). While studies on their impact on local ecology are ongoing, there is concern that the dense mats of M. strigata in the Kranji mudflats would reduce the amount of space available for the endangered horseshoe crabs to burrow into the sand for seeking shelter and laying their eggs. At the same time, the effect of M. strigata in displacing the native Asian green mussel is unclear, which could have an economic impact to local fish farms that culture, harvest and sell them.

Marine Litter and Debris

As an intertidal guide, something I am sadly quite used to is the sight of trash. This is another example of a ‘slow violence’ problem. Trash is harmful in two ways to animals – wildlife could eat and subsequently suffocate or get entangled in them, which causes severe injuries and deaths. Trash could also get mistaken for food, and in excessive amounts, animals could die from starvation as their stomachs are filled up with plastic debris rather than proper nutrition.

Of course, as ecosystems are interconnected, it comes back to us: when plastics begin to break down in the sea, they release toxic substances and micro-plastics that could enter the food chain via our seafood, and affect our body’s internal systems in unknowable, indeterminable ways.

Concluding Thoughts

Extreme weather events, land reclamation, the rise in plastic pollution and the increase in numbers of invasive species being introduced meant that our coasts have experienced dramatic transformations in the last 200 years, resulting in the loss of habitats and their marine species. At the same time, there is room for cautious optimism, for coastal flora and fauna appear to be persisting and more resilient than we thought.

While marine ecosystems have long been hidden from the view of regular Singaporeans, those concerned about the health of Singapore’s coastal environments need to find a way to reestablish connections to the sea, be it by intertidal explorations, or going on a beach cleanup – or better yet, both combined. Such efforts of education and direct action via beach cleanups are part of a network of solutions to mitigate climate change, restore ecosystems, and preserve heritage-based livelihoods.