Why Some Women and Not Others?

Published

October 2, 2022

By

Team

In any given society, not all women are equally oppressed, and some women benefit more from feminism than others.

This is because some women are privileged by (for example) their social class, race, or ethnicity. Women aren’t solely defined by their gender, and taking these other factors into account is called intersectional feminism.

Opponents of intersectionality claim that it dilutes the focus of ‘pure’ feminism, but this ignores the fact that women experiencing multiple forms of prejudice cannot compartmentalise them. Intersectional feminism can help us protect all women, and not just a privileged few. Below, we outline some of the ways class and race can impact women’s lives.

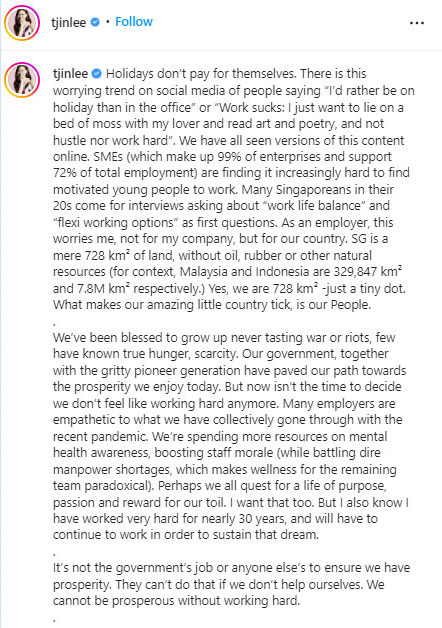

PR agency co-founder Tjin Lee went viral in July 2022 for an Instagram post criticising young workers speaking out against hustle culture.

(Tjin Lee)

Orchard Road’s Lucky Plaza has long been a gathering place for the Pinay FDW community, who account for close to one-third of FDWs in Singapore (Wikimedia Commons)

Class

When many people think of feminist history, they mostly recall quotes or speeches by educated women such as Michelle Obama and Hillary Clinton, while the contributions of working-class women are forgotten. This may be because the means of advocacy available to poor, less educated women — mostly strikes and sometimes violent protests — are less palatable to people than the dignified eloquence of upper class feminists.

This selective history has led many to believe in a false sense of trickle-down feminism, i.e., that when wealthy women politely and articulately win rights, that these gains will naturally trickle down to working-class women in far more desperate positions (so don’t bother striking, and get back to work, please).

Singapore is no exception to this, as 2021’s Year of Celebrating SG Women proved. A historic White Paper and yearlong Conversation on Women’s Development were launched, and high-achieving Singaporean women were profiled in the media as embodiments of progress.

Yet, despite there being 300,000 female foreign domestic workers (FDWs) living and working long-term in Singaporean households, FDWs were frozen out of the dialogue. In Singapore, they are neither protected by the Women’s Charter nor the Employment Act; their exclusion from the latter, in particular, is attributed to the undervaluing of women’s domestic labour. Despite accounts of poor working conditions and abuse, FDWs’ welfare was not addressed at all in the landmark White Paper.

FDWs’ cultural invisibility is a stark contrast to the attention paid by Singapore society to wealthy career women or girl bosses, whose successes provoke little consideration of continuing inequalities that pose urgent threats to working-class women’s lives.

Can we really be said to celebrate all women, without honouring the thousands who help keep our homes and care for our loved ones?

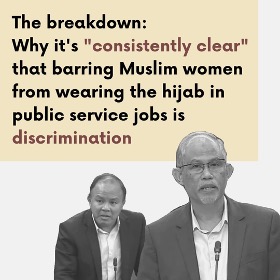

Social media can provide minority women a platform for their experiences. For example, @beyondhijabsg is a grassroots effort to sensitise the wider Singapore public to the struggles of Muslim women. (beyondhijabsg)

Race/ethnicity

Just as women’s poverty can be deflected as a labour and not a feminist issue, the unique challenges faced by racial or ethnic minority women are often neglected or even amplified.

In much of western reportage, sexism faced by ethnic Muslim women is depicted as solely an ‘inside’ issue within Muslim communities, and not something also perpetrated by those outside Islam. As such, misogyny and ethnic prejudice against Muslim women from wider society goes unexamined.

In late-2021, an EU court approved discriminatory hijab bans in workplaces. While it’s tempting to frame the hijab debate as a purely ethno-religious one, it is not much different than Norwegian female handballers being fined by the European Handball Federation for refusing to wear bikini shorts in competition: in both cases, women’s bodily autonomy and freedom of choice is compromised. Only the latter incident, however, went viral in feminist spaces on social media.

Echoes of Europe’s hijab debate can even be found in multicultural Singapore, where department store TANGS made headlines in 2020 for demanding that a part-time store promoter remove her hijab at work “for the sake of professionalism”. Insofar as the intense scrutiny of women’s attire in the workplace has been identified as a major barrier to gender equality in the workplace, the hijab debate is inseparable from the broader movement to increase women’s agency in society.

The TANGS incident was framed by the local media solely as a topic of religious sensitivity but not feminist debate, ignoring the lived experience of people who are both women and Muslim. It’s worth questioning: what makes a pencil skirt of any length more relevant to feminist discussion than a hijab?

Blessing or curse?

Women are diverse. Some women choose marriage and children, others don’t. Some women subscribe to organised religion, others don’t. Some women live as minorities and outsiders in their home countries, others don’t. And so on.

We can choose to understand these differences as a source of complication that waters down ‘true’ feminism. Or, we could see them as a cherished sign of the breadth of female experience.

‘Intersectionality’ can sound complex, daunting, and even threatening in how it forces us to consider who or what feminism deems worthy of fighting for. But by learning to embrace and hold space for different experiences, we can authentically advocate for all, not just some, women.