How Women Look

Published

May 20, 2022

By

Tracey Toh

In Plain View

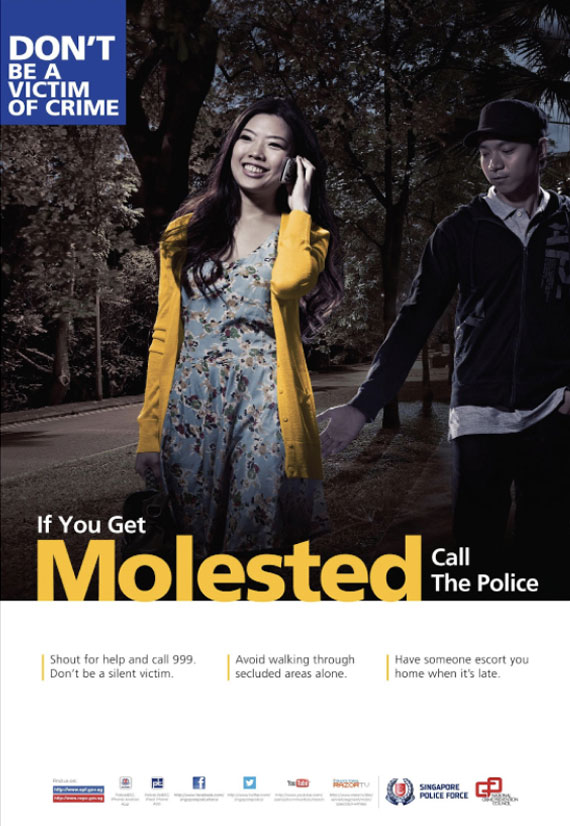

Images from @singaporepoliceforce.

If you’ve ever wanted to know how the world looks at women, you would not need to look very far.

From lewd comments about female hires, to the comparison of women’s bodies to pieces of meat, many people perceive women as part of the scenery. Society’s objectifying view of women is evident everywhere.

This view is built into our urban environment, for instance, in these Singapore Police Force posters which feature a shady man literally emerging from the shadows to grope a passing woman. These images serve as a constant warning, on our daily transit, that women are vulnerable to the objectifying stares of men.

Of course, these are only the most egregious examples of how women are sexualised. But this way of seeing women also turns up in more subtle, seemingly innocuous practices.

I’ve noticed that men my age tend to introduce their female partners by describing them as “pretty”. They may go on to add that their partners are “smart”, “skilled” or “kind”, but they usually mention beauty first.

It is an affectionate gesture to show their appreciation for someone they care about, that also says a lot about what society values in women—visual appeal, before all else.

Female, Framed

Female, Framed

This focus on women’s physical attractiveness finds its most explicit form in cinema, which has long developed a set of formal codes for portraying women.

In 1975, film scholar Laura Mulvey identified a dominant, gendered mode of vision operating across Hollywood. She called this the male gaze.

For Mulvey, the male gaze is as unmistakable as it is ubiquitous. It is a sexualising, objectifying outlook, that does not always rely on overt sexuality or nakedness. It works simply by highlighting a woman’s physical beauty, by offering her up as a figure to be enjoyed. The female character may have other qualities, she may be strong, complex or empowered, but she is always alluring.

Calling it the male gaze is instructive as well. To gaze is not merely to look; it is to regard someone intently, with a kind of fascination and pleasure. The camera lingers on certain profiles and angles, on legs or hair or shoulders, to show the female star off to full effect. The viewer is positioned as a voyeur, gazing upon the woman who practically beckons.

Looking for Likes

Images from @novitalam, @euniceannabel, and @naomineo_.

Looking for Likes

The influence of the male gaze is hardly limited to men.

To look at a woman is also to see through the eyes of men. As women, many of us internalise the male gaze. It disciplines us, not so obviously by dictating exactly what to wear or what poses to strike, but by modelling a way of picturing ourselves.

Most of us are familiar with a certain Singapore influencer look. In our hyper-visual contemporary culture, women produce and post images for profit. We turn the camera on ourselves, and market these images primarily to other women. We might imagine that this gives us more creative license over our images, and more control over our public profiles. Yet, across social media, the images that earn the most likes have a remarkably generic quality.

To appeal to the widest audience, it is easier to fall back on the postures, expressions and silhouettes that are tried and tested. These visual conventions are reproduced because they are instantly legible; anyone looking at the resultant image would appreciate it as a display of female beauty.

Another Line of Sight

Another Line of Sight

For both men and women, the male gaze has become the default mode of perception, priming our expectations as audiences and shaping how we see ourselves.

Resisting the male gaze requires a conscious effort, and will take more than merely avoiding overt sexualisation, or making assertions of girl power. If we want to break away from the orbit of the male gaze, we need a new way of seeing and a new visual language.

But trying to articulate an alternative, or female gaze, lands us in tricky terrain.

The female gaze is itself a troubling term, because it implies a single, monolithic vision. TV critic Emily Nussbaum is wary of the female gaze, “with its essentialist hint that women share one eye”.

There are indeed different ways to create new cultural norms with a critical consciousness of gender. The women scriptwriters of K-dramas are investing on-screen relationships with more emotional intimacy. Female leads are making their blemishes visible in movies, redefining how we understand beauty or eschewing an emphasis on beauty altogether.

The contours of the female gaze, or gazes, are still unclear, and perhaps the opportunity we have is in preserving that unformed, ill-defined way of seeing women. In doing so, we might cultivate a vision that is elastic enough to accommodate multiple, even contradictory approaches to sexuality, physicality and femininity.

This essay is part of a series by our youth resident Tracey Toh that explores what it means to be a woman in contemporary society.