From Forest to Longkang: Resilient Pythons

Published

February 6, 2023

By

Neo Xiaoyun

The question of why pythons are still around in our ‘modern, urban city’ is often posed in deep exasperation. The implicit assumption is that they should have been extirpated long ago with all the other large predators — the Malayan tiger and clouded leopard. Instead, they are the most common type of snakes found in Singapore. Curiously the python’s thriving success in our metropolis seems to be a product of urban development.

A Historical View

Let’s start 200 years ago. Naturally, one can imagine, pythons were commonplace in pre-colonial Singapore. With the early settlement of Chinese and Malay gambier and pepper farmers from the Malay world, and the beginnings of small-holder farming, pythons were not only in forests but continued to thrive with abundant food sources near farms on chickens, ducks and other poultry.

The colonial government began to take several “practical measures” to promote the elimination of the “savage beasts”. The methods were truly varied — for strong was their motivation. They wanted to ensure the possibility of further inland expansion away from the port. Accordingly, the amount of monetary reward for a successful kill was attractive. The reward they offered — “depended on the animal and its size… For snakes, the monetary payouts were based on their length. Those over 14 feet (4 meters) were worth $5 [about $120 in 2022] “— gives us a glimpse of how many pythons and other snakes were extirpated this way.

From Forests, to Unlikely Urban Homes

Today, the python’s persistence is testament to the success of urban planning and urban infrastructure. You would be familiar with the massive projects to flood-proof our waterways, which is really a way of saying that Singapore’s engineers expanded, deepened, and straightened existing flows of water. We’ve poured concrete into small trickles, natural streams, and rainfed rivers, transforming them into a systematic configuration of shallow drains, water pipes, and monsoon canals. This process destroyed many freshwater and swamp forest habitats, but at least a few creatures benefited.

Most structures are shaped as valleys, half-moon cylinders or troughs. This gives the python great physiological advantage and accessibility over many other types of biodiversity. Pythons are strong swimmers and can travel using drains as their highways to get to their prey, such as frogs, toads, rats, lizards, and some fish, that have also integrated and adapted to our urban systems. This abundance of sustenance in drain ecosystems keeps pythons within drains.

In other words, Singapore has inadvertently created a snake friendly environment via large rain canals. And this is a mutually beneficial relationship that we have stumbled upon. By their diet preferences, snakes exert a natural population control on the numbers of rats in our city. This forms a natural waste management method within the same urban system that uses these large monsoonal drains to mitigate floods.

Fast Food in the City

At the same time, pythons will eat anything they can catch. My friend Pamela said it best. “If you were a human, and had to prepare your own food which takes two hours or simply could tabao McDonald’s or anything from Grab delivery, what would you choose?” In an urban setting, pythons thus develop a new taste for pet and community cats, on top of its regular fare.

As we learn to draw sensible connections to pythons’ choice of habitats today, and think from the pythons’ perspective, we can understand their propensity to live in urban environments, from accessibility to easier targets, to facilitating the movements through canals that span across the island. Their thriving speaks to their resilience adapting to life in the urban infrastructure that we created (not for them). They are among the few large predators and carnivores that have survived, perhaps by their taking advantage of new niches, moving from forested areas into today’s concrete canals.

An essay on human-macaque interactions in Eating Chilli Crab in the Anthropocene reflected that “We are already deeply entangled in a multispecies community, even if we don’t always acknowledge it. As such, the challenge is for us to be more intentional about creating mutually beneficial and shared spaces for all species.” This applies to pythons and other large and small animals that still inhabit our urban city.

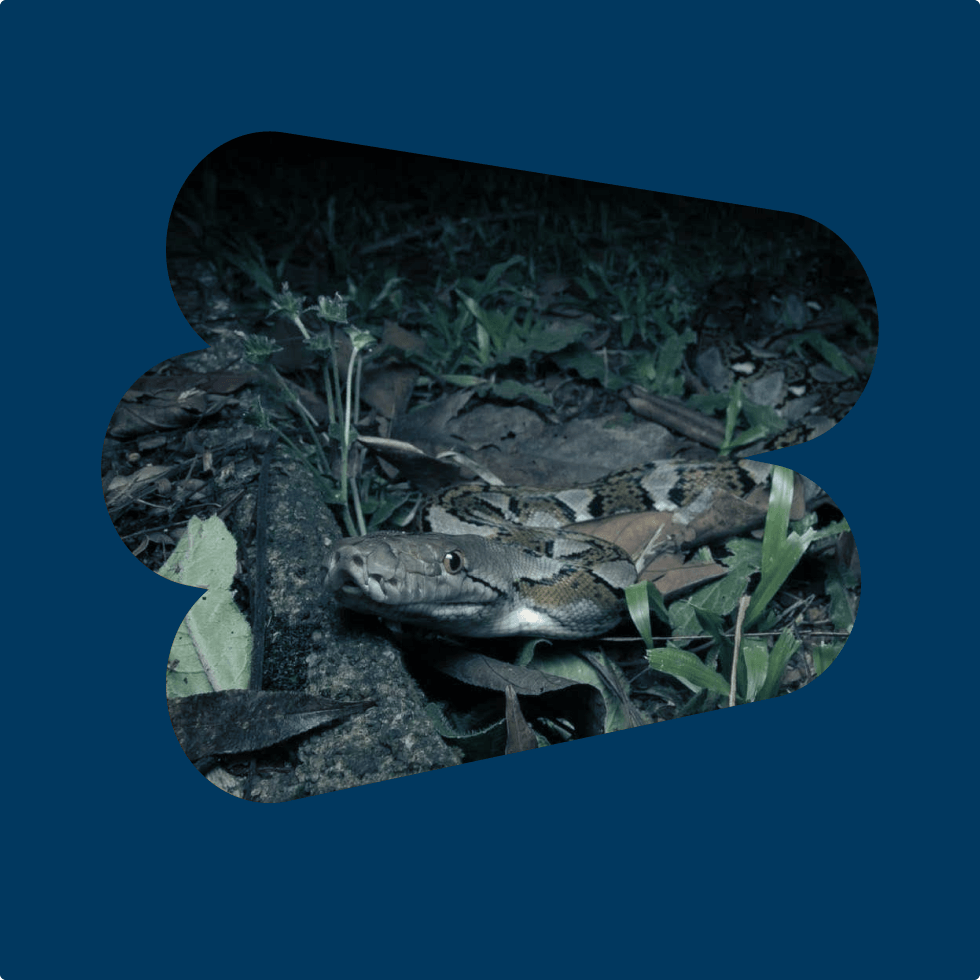

November 2021: Python in large storm drain, less than 100 metres away are a church, stretch of restaurants and landed property. Photo by Neo Xiaoyun.

Final Thoughts

As a first step, it begins with paying attention and becoming more attuned to one’s environment. On two occasions, I had been distracted, speaking to a fellow wildlife guide. I was about to take another step when something snapped in me. I stopped, looked down, illuminated the path with my torchlight, and my heart was in my mouth, for there it was — a long iridescent python, half a metre away, head in a tight coiled S-shape.

That night reminded me to always pay attention when I walk in spaces near storm drains at night. As we are increasingly living in integrated spaces with nature that may result in more wildlife encounters, it is important to be mindful of their presence amidst our urban city, which would go some way to mitigating human-wildlife conflicts.

The author would like to thank Pamela Ng for her conversations, thoughts and insights have been a source of inspiration for this piece. Do check out Pam’s work here: @wildlife.pamdemic on IG (WIP) / LinkedIn