Land-use Transformation and the Loss of Nature in Singapore

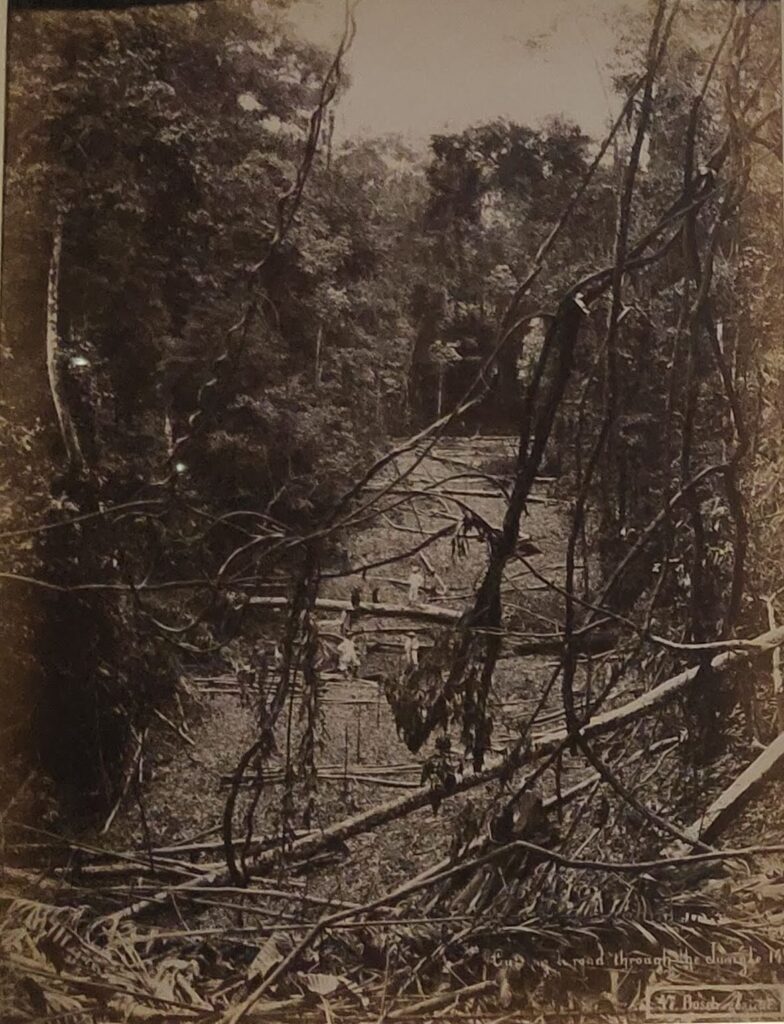

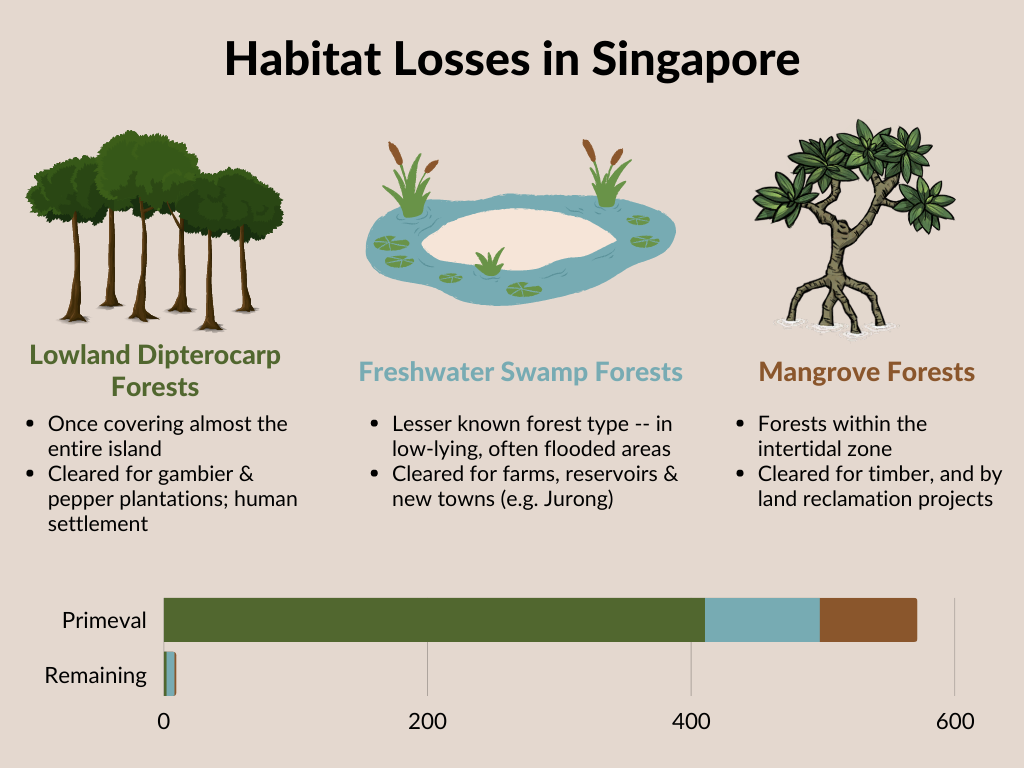

Lowland dipterocarp forest

Before

Pre-colonial Singapore

After

Present day

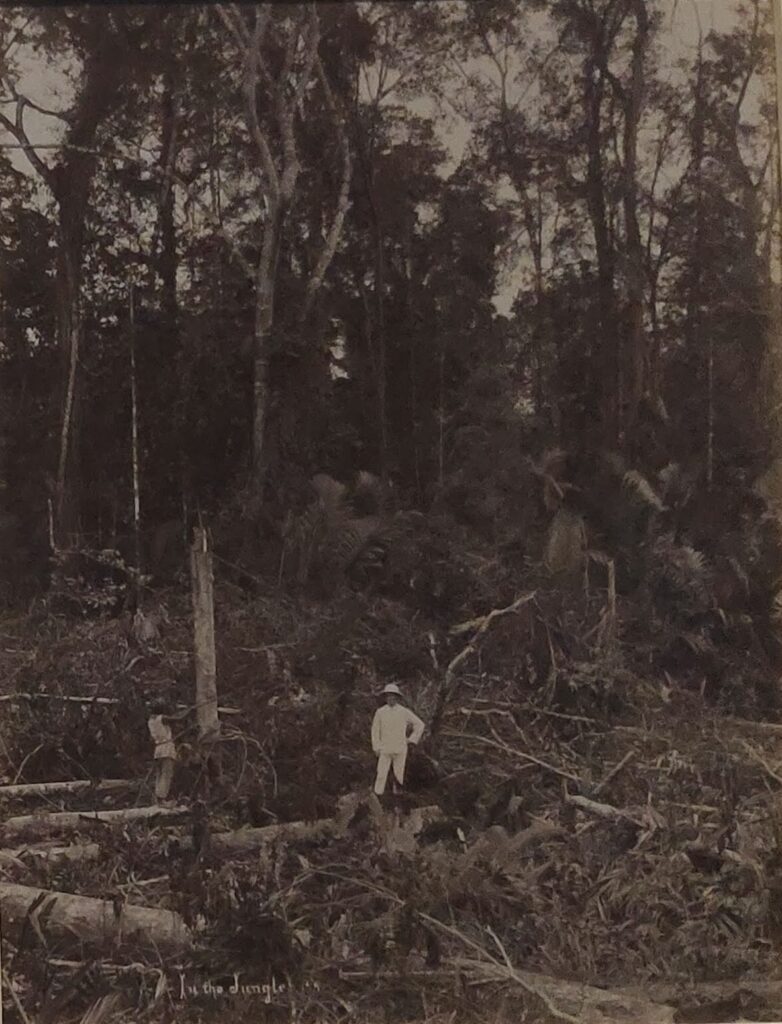

Forests quickly became overharvested for timber. The first primary crops grown in Singapore – gambier and pepper – demanded huge amounts of timber to process.

Today, an estimated 0.5% of the original lowland dipterocarp forests remain.

Freshwater swamp forest

Before

Pre-colonial Singapore

Often found in low-lying coastal plains, where periodic inundation by slow-flowing forest streams created a floristically and faunistically distinct habitat and ecosystem. Their namesake distinguishes them from saltwater mangrove swamps.

5% of Singapore was freshwater swamp forest.

After

Present day

These forests were significantly depleted. The brackish, alluvial soils — think those for rice terraces of Bali — became highly desired for farming. Mandai’s swamp forest was converted into reservoirs including Upper Seletar Reservoir during the colonial period, while the Jurong swamp forests were cleared for Jurong Industrial Estate and housing developments in the 1960s.

This leaves the Nee Soon swamp forest the last remnant of the freshwater swamp forest formation in Singapore.

Mangrove forests

Before

Pre-colonial Singapore

After

Present day

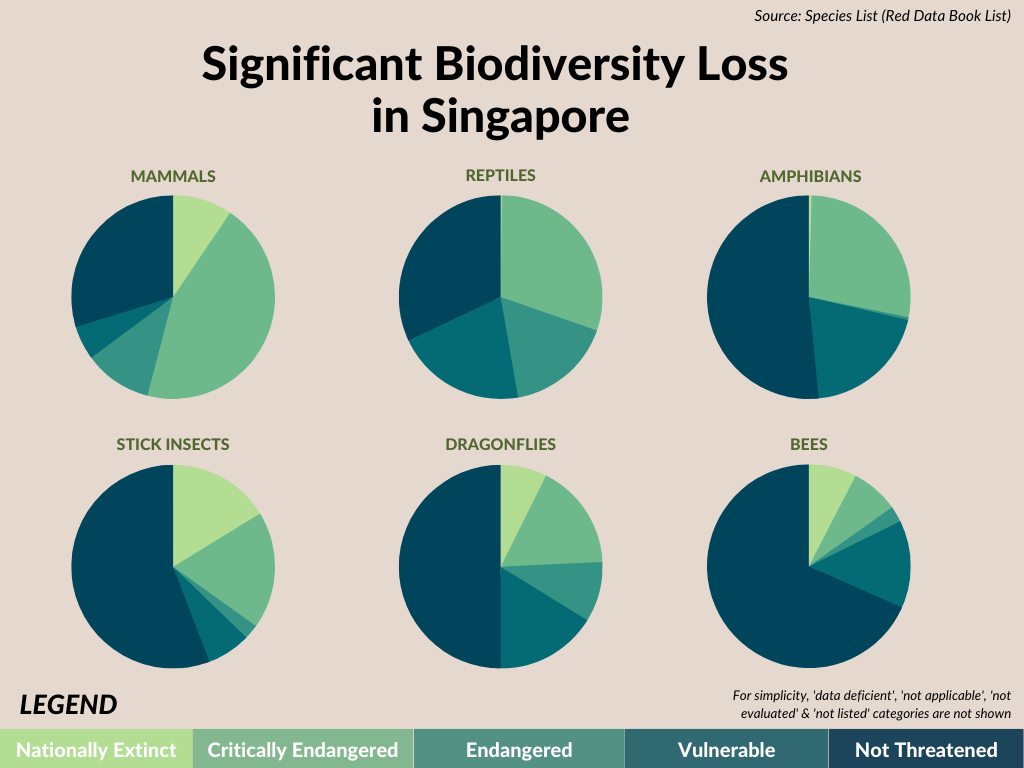

The biodiversity

As forests were cleared, ecosystems became fragmented, reducing the available habitat for flora and fauna. Faunal species which were studied more were estimated to suffer an extinction rate of 73%, with at least 100 bird species, twenty freshwater fish species and several species of mammal lost.

Indochinese leopards, hairy-nosed otters and cream-coloured giant squirrels were extirpated (i.e. became locally extinct) from the forests. The banded leaf monkey, Sunda pangolin, leopard cat and Malayan porcupine survived in small numbers in remaining fragmented patches. The greater mouse-deer was extirpated on the Singaporean mainland, but remains on the small, outlying, semi-forested island of Pulau Ubin.

Across the mudflats, the dugong — once a common sight in our intertidal zones — drastically reduced in numbers and moved away to friendlier waters of Johor.

Of the 195 breeding bird species ever recorded in Singapore over the last 200 years, 58 (about 30%) are known to have gone extinct. The losses include the trogons, broad-bills, nine species of woodpeckers, four species of kingfishers, two species of barbet and two species of babblers. Among the critters, the Singapore freshwater crab survives in small, disconnected forest streams in the heart of the remaining primary forest.

As Timothy Barnard astutely observed, in Singapore, “developing a colonial port essentially meant transforming, in biological terms, a ‘multi-species habitat’ into a more simplified landscape that would fulfill the needs of a western trade company and the humans that served it.” The physical changes in our landscape had significant and very drastic resonances on biodiversity and native wildlife in Singapore, especially given how distinct flora and fauna inhabit the three habitats. For instance, species found at Nee Soon Swamp are generally not found in lowland forests of Bukit Timah, and vice versa; the remaining biodiversity is thus limited to small, disjoint patches of forest.

This story is not confined to Singapore, for globally, we are living through the single greatest biodiversity loss in human history. During this “sixth mass extinction” event, the human-driven extinction of species is estimated to be between 1,000 and 10,000 times higher than the natural (or background) extinction rate.

Conservationists worry about the loss of intrinsic motivation among the younger generation to reverse the trend of rapidly diminishing global biodiversity. To catalyse awareness and action towards biodiversity loss, we should teach our history of loss and extirpations in the local physical environment, and biodiversity in mainstream education.

Moreover, we should recognise the remaining 0.5% to 6.5% of Singapore’s original habitats as precious natural assets, deserving strict protection for conservation and restoration.

Sources

- O’ Dempsey, Tony. 2014. “Singapore’s Changing Landscape since c. 1800”. In Nature Contained, edited by Barnard, Timothy. NUS Press